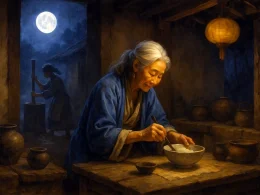

Trees sway in the crisp late autumn breeze;

I sit with wine, companion to passing time.

My face, drunk, glows like leaves touched by frost —

A red that speaks of autumn, never of spring’s prime.

Original Poem

「醉中对红叶」

白居易

临风杪秋树,对酒长年人。

醉貌如霜叶,虽红不是春。

Interpretation

This short piece is traditionally ascribed to Bai Juyi's later years. While its precise date is unknown, the profound autumnal spirit and clear-eyed insight it conveys undoubtedly belong to the poet's old age, following a lifetime of official ups and downs, when he had settled into a life of quiet retirement. By this time, the poet had long shed the sharp, public-minded zeal of his youth aimed at "helping the world." He had turned instead to the daily cultivation of self ("preserving one's own integrity"), contemplating the simple truths of existence. This five-character quatrain resembles a spare yet profound self-portrait. Through the interplay of deep autumn, frost-tinted leaves, drunkenness, and an aged face, it achieves a composed, poetic meditation on the inevitable fact of bodily decay.

First Couplet: “临风杪秋树,对酒长年人。”

Lín fēng miǎo qiū shù, duì jiǔ chángnián rén.

Facing the wind, a tree in deepest autumn's hour; / Facing the wine, a man of many a year gone sour.

The opening lines sketch a still scene of man and landscape facing each other. "Facing the wind" (outward) and "facing the wine" (inward) frame the poet’s stance between nature and self. "A tree in deepest autumn" fixes the season as late fall, a time of withering and stillness; "a man of many a year" frankly states he has entered life’s twilight. Tree and man both exist in life’s autumnal phase, creating a parallel, reflective relationship. The word "facing" is both action and state of mind—the poet is not merely viewing the scene but engaging in a silent dialogue with the autumn tree about life’s latter stage. Wine here is companion and catalyst, aiding a journey toward unadorned self-awareness.

Second Couplet: “醉貌如霜叶,虽红不是春。”

Zuì mào rú shuāng yè, suī hóng bú shì chūn.

This wine-flushed face is like a leaf touched by frost's stain; / Red, yes—but not the red that belongs to spring's domain.

This couplet is the poem’s core—a superb metaphor that articulates the essence and flavor of aging. The poet regards his reflection and sees the wine-induced flush precisely mirroring the bright crimson of a frosted autumn leaf. The following five words—"but not the red that belongs to spring"—act as a cold corrective, dispelling the surface similarity to reveal the fundamental difference. The leaf’s red is life’s final, coerced blaze—splendid yet terminal. The drunken flush is a brief, artificial surge—forced, a kind of mask. Both are "red," but this redness lacks the vitality, budding hope, and renewal of "spring"; it contains only the maturity, starkness, and clear-eyed acknowledgment of an ending that belongs to "autumn." The metaphor is perfect in form and spirit, blending aesthetic beauty with a clear, unflinching, and quietly sad truth.

Holistic Appreciation

The poem’s power lies in the tension between its extremely concise form and its rich inner substance. In twenty characters, it builds three layers of meaning: The first is the immediate scene (autumn tree) and act (facing wine), presenting a concrete moment from later life. The second is the brilliant metaphor (drunken face like frosted leaf), linking a human state with a natural phenomenon in a vivid image. The third is philosophical insight (red, but not of spring), leaping from the image to a fundamental inquiry, revealing the deep矛盾 between appearance and essence, the transient and the enduring, youth and age. The four lines move from outer to inner, from scene to person, from form to spirit, ending on a quiet sigh regarding life’s truth—a complete arc from observation to understanding.

Artistic Merits

- A Profound and Subversive Metaphor: The comparison of a “wine-flushed face” to a “frosted leaf” inverts a poetic cliché (where a “face like peach blossoms” signifies youth). This inventive yet apt analogy captures the poignant condition of one who “mirrors spring while dwelling in autumn”—transforming a familiar concept into something uncommon and deeply resonant.

- Incisive Contrast and Definitive Reversal: The poem severs the instinctive symbolic link between “red” (colour of vitality) and “spring” (season of renewal) with the decisive phrase, “but not…”. This powerful negation generates a lucid, almost stark recognition, carrying significant intellectual force by challenging conventional perception.

- Extreme Conciseness with Evocative Power: The poem employs no obscure diction or superfluous words. Ordinary terms—“deepest autumn,” “many a year,” “frosted leaf”—are burdened with the immense weight of time and mortality. Emotion remains restrained; a quiet sadness is enfolded within the calm description and precise metaphorical frame.

- The Blurring of Self and World: The poet contemplates his own state by merging completely with the natural image, achieving a unity where observer and observed become indistinguishable. This is not simple personification, but a profound resonance between the rhythms of human life and the cycles of the natural world.

Insights

The poem shows the fusion of Bai Juyi’s late poetics and life philosophy. It gazes directly at physical decay with a peaceful, clear-eyed, even slightly detached gaze. The "red" in the poem is a clear-sighted acknowledgment: it does not avoid the resemblance between an old man’s flush and a leaf’s red, nor does it pretend this red means spring’s return.

The insight it offers is this: True openness and wisdom lie not in denying or prettifying decline, but in recognizing its inevitability and still affirming a quiet beauty and dignity proper to autumn. The frosted leaf’s red, though not spring’s, has its own intensity and stillness, born of enduring the elements. Later life, though lacking youth’s vigor, can possess the clarity of insight and the composure of acceptance. Bai Juyi shows that each life stage has its unique color and worth. The key is to see it truthfully, accept it calmly, and give it poetic form. This acceptance and contemplation of life’s full journey is perhaps the deepest expression of his philosophy of "retired living" in old age.

About the Poet

Bai Juyi (白居易), 772 - 846 AD, was originally from Taiyuan, then moved to Weinan in Shaanxi. Bai Juyi was the most prolific poet of the Tang Dynasty, with poems in the categories of satirical oracles, idleness, sentimentality, and miscellaneous rhythms, and the most influential poet after Li Bai Du Fu.