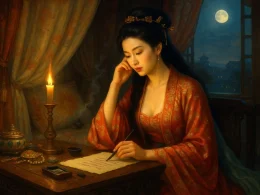

The Shangyang Palace maid,

Her hair grows white, her rosy cheeks grow dark and fade.

The palace gate is guarded by eunuchs in green.

How many springs have passed, immured as she has been!

She was first chosen for the imperial household

At the age of sixteen; now she's sixty years old.

The hundred beauties brought in with her have all gone,

Flickering out through long years, leaving her alone.

She swallowed grief when she left home in days gone by,

Helped into the cab, she was forbidden to cry.

Once in the palace, she'd be favored, it was said;

Her face was fair as lotus, her bosom like jade.

But to the emperor she could never come nigh,

For Lady Yang had cast on her a jealous eye.

She was consigned to Shangyang Palace full of gloom,

To pass her lonely days and nights in a bare room.

In empty chamber long seemed each autumnal night;

Sleepless in bed, it seemed she'd never see daylight.

Dim, dim the lamplight throws her shadow on the walls;

Shower by shower on her windows chill rain falls.

Spring days drag slow;

She sits alone to see light won't be dim and low.

She's tired to hear the palace orioles sing and sing,

Too old to envy pairs of swallows on the wing.

Silent, she sees the birds appear and disappear,

And counts nor springs nor autumns coming year by year.

Watching the moon o'er palace again and again,

Four hundred times and more she's seen it wax and wane.

Today the oldest honorable maid of all,

She is entitled Secretary of Palace Hall.

Her gown is tightly fitted, her shoes like pointed prows;

With dark green pencil she draws long, long slender brows.

Seeing her, outsiders would even laugh with tears;

Her old-fashioned dress has been out of date for years.

The Shangyang maid, to suffer is her fate, all told;

She suffered while still young; she suffers now she's old.

Do you not know a satire spread in days gone by?

Today for white-haired Shangyang Palace maid we'll sigh.

Original Poem

「上阳白发人」

白居易

上阳人,上阳人,红颜暗老白发新。

绿衣监使守宫门,一闭上阳多少春。

玄宗末岁初选入,入时十六今六十。

同时采择百余人,零落年深残此身。

忆昔吞悲别亲族,扶入车中不教哭。

皆云入内便承恩,脸似芙蓉胸似玉。

未容君王得见面,已被杨妃遥侧目。

妒令潜配上阳宫,一生遂向空房宿。

宿空房,秋夜长,夜长无寐天不明。

耿耿残灯背壁影,萧萧暗雨打窗声。

春日迟,日迟独坐天难暮。

宫莺百啭愁厌闻,梁燕双栖老休妒。

莺归燕去长悄然,春往秋来不记年。

唯向深宫望明月,东西四五百回圆。

今日宫中年最老,大家遥赐尚书号。

小头鞋履窄衣裳,青黛点眉眉细长。

外人不见见应笑,天宝末年时世妆。

上阳人,苦最多。

少亦苦,老亦苦,少苦老苦两如何!

君不见昔时吕向美人赋,

又不见今日上阳白发歌!

Interpretation

This poem is the seventh in Bai Juyi’s Fifty New Music Bureau Poems, composed around 809 CE. The Tang palace women's system was exceptionally harsh; once selected for service, they were confined for life, never permitted to leave. Historical records note thousands of such women under Emperor Taizong, with the number swelling to tens of thousands by Emperor Xuanzong's reign. The vast majority spent their lives "dwelling in vacant rooms," becoming the most silent casualties of the imperial institution. Serving as a Reminder and deeply committed to the Confucian ideal of governance for the people, Bai Juyi explicitly stated his purpose in composing the New Music Bureau Poems was to write "for the ruler, for the ministers, for the people, for all things, and for events." This poem takes as its subject a Shangyang Palace attendant who "entered at sixteen and is now sixty." Through a detailed depiction of her forty-four sequestered years, it composes a biography for legions of forgotten palace women and delivers a profound indictment of a system that mutilates human nature, embodying Bai Juyi's realist creed of "singing only of the people's sufferings."

Section One: 上阳人,上阳人,红颜暗老白发新。绿衣监使守宫门,一闭上阳多少春。

Shàngyáng rén, shàngyáng rén, hóngyán àn lǎo báifà xīn. Lǜyī jiān shǐ shǒu gōngmén, yī bì Shàngyáng duōshǎo chūn.

Lady of Shangyang, Lady of Shangyang, / Your bright face fades in shadow, new white hairs thread your brow. / Green-coated guards keep watch at the palace gate; / Once shut, how many Shangyang springs have passed their date?

The poem opens with a sorrowful, direct address. The juxtaposition of a fading youthful face and newly sprouting white hairs instantly spans a lifetime of concealed decay. The "Green-coated guards" symbolize her imprisonment, while the poignant question—"how many… springs have passed?"—frames her personal tragedy within the implacable mechanics of the institution, establishing the poem's plaintive and somber tone.

Section Two: 玄宗末岁初选入,入时十六今六十。同时采择百余人,零落年深残此身。

Xuánzōng mò suì chū xuǎn rù, rù shí shíliù jīn liùshí. Tóngshí cǎizé bǎi yú rén, língluò nián shēn cán cǐ shēn.

In our late Sovereign’s final years, first chosen to attend; / I entered at sixteen, and now sixty is my end. / A hundred more were gathered, chosen side by side; / Scattered by the years, this ruined self is all that has survived.

The poet measures a stolen life with cold arithmetic. The forty-four years between "sixteen" and "sixty" represent a hollowed existence. The reduction from "A hundred more" to a single "ruined self" speaks not only of her isolation but implies the silent obliteration of countless others who shared her fate, amplifying the tragedy’s dreadful commonality.

Section Three: 忆昔吞悲别亲族,扶入车中不教哭。皆云入内便承恩,脸似芙蓉胸似玉。

Yì xī tūn bēi bié qīnzú, fú rù chē zhōng bú jiào kū. Jiē yún rù nèi biàn chéng ēn, liǎn sì fúróng xiōng sì yù.

I recall how I swallowed grief, parting from my kin; / Helped into the carriage, I was forbidden to weep within. / All promised, once inside, the imperial grace I’d find, / My face a lotus bloom, my bosom fair and jade of mind.

Memory returns to the moment of entry. "Swallowed grief" and "forbidden to weep" reveal the brutal suppression of natural feeling demanded by the system. The lavish praise of her beauty—"face a lotus bloom"—becomes bitterly ironic,暗示 that the very attributes deemed her fortune sealed her misfortune, transforming her into a commodity.

Section Four: 未容君王得见面,已被杨妃遥侧目。妒令潜配上阳宫,一生遂向空房宿。

Wèi róng jūnwáng dé jiànmiàn, yǐ bèi Yáng fēi yáo cèmù. Dù lìng qián pèi Shàngyáng gōng, yīshēng suì xiàng kōng fáng sù.

Before I could gain my sovereign’s glance, earn his regard, / Consort Yang had fixed on me her jealous gaze from afar. / Her envy had me secretly assigned to Shangyang’s keep; / A lifetime thus condemned to lodge in rooms vacantly deep.

The specific cause of her ruin is named: palace intrigue. The verb "assigned" exposes the arbitrary, shadowy exercise of power. The line "A lifetime thus condemned to lodge in rooms vacantly deep" reads as a final sentence,宣告 the total annihilation of her future from that moment forward.

Section Five: 宿空房,秋夜长,夜长无寐天不明。耿耿残灯背壁影,萧萧暗雨打窗声。

Sù kōng fáng, qiū yè cháng, yè cháng wú mèi tiān bù míng. Gěnggěng cán dēng bèi bì yǐng, xiāoxiāo àn yǔ dǎ chuāng shēng.

Lodging vacant rooms, the autumn nights drag on; / Sleepless through the long dark, waiting for a dawn that won’t be drawn. / A guttering lamp throws my hunched shape upon the wall; / A soughing, secret rain taps a grim tattoo, that’s all.

Sensory detail maps the contours of her desolation. The endless "autumn nights" are both real and psychological. The interplay of the fading lamp’s sight and the secret rain’s sound constructs a perfectly sealed,循环 cell of time and space from which there is no escape.

Section Six: 春日迟,日迟独坐天难暮。宫莺百啭愁厌闻,梁燕双栖老休妒。

Chūnrì chí, rì chí dú zuò tiān nán mù. Gōng yīng bǎi zhuàn chóu yàn wén, liáng yàn shuāng qī lǎo xiū dù.

Spring days are slow; sitting alone, dusk will not descend. / A hundred palace oriole trills—their joy I’ve grown to hate; / Beam-swallows perched in pairs—too old for envy now, my fate.

Even spring, a season of renewal, offers no relief. Her perception of time is uniformly distorted: days are as interminable as nights. Her厌闻 of birdsong and the extinction of envy for paired swallows reveal the final, lethal toll of prolonged isolation: the erosion of all connection, even the capacity for painful longing.

Section Seven: 莺归燕去长悄然,春往秋来不记年。唯向深宫望明月,东西四五百回圆。

Yīng guī yàn qù zhǎng qiǎorán, chūn wǎng qiū lái bú jì nián. Wéi xiàng shēn gōng wàng míngyuè, dōngxī sìwǔ bǎi huí yuán.

Orioles come, swallows go, in lasting quietude; / Springs depart, autumns arrive, I’ve lost the tally of the year. / Only toward the deep palace I watch the bright moon’s face— / East to west, four or five hundred times, it has completed its cycle in this place.

Nature’s cycles mock her stasis. "I’ve lost the tally of the year" marks the zenith of her dislocation from time. The moon becomes her sole calendar, and the brutal statistic—"four or five hundred times" (over 500 full moons in 44 years)—transforms relentless, empty duration into a crushing, countable weight.

Section Eight: 今日宫中年最老,大家遥赐尚书号。小头鞋履窄衣裳,青黛点眉眉细长。外人不见见应笑,天宝末年时世妆。

Jīnrì gōng zhōng nián zuì lǎo, dàjiā yáo cì shàngshū hào. Xiǎo tóu xiélǚ zhǎi yīshang, qīng dài diǎn méi méi xì cháng. Wàirén bú jiàn jiàn yīng xiào, Tiānbǎo mò nián shíshì zhuāng.

Today, in the palace, I am the eldest one; / Our sovereign, from afar, grants the hollow title “Secretary,” as if done. / I wear small-toed shoes, gowns with a narrow waist’s confine, / Blue-black kohl dots brows I pencil to a slender line. / Unseen, outsiders surely would break out in scornful mirth— / This fashion died with Tianbao, the last era on earth.

Her status as "the eldest one" is met with the empty honorific "Secretary," a辛辣讽刺 that highlights the system’s cynical hypocrisy. The meticulous description of her anachronistic Tianbao-era fashion is devastating: her body has aged, but her social and aesthetic existence is permanently frozen at the moment of her entombment, making her a living relic, an object of potential ridicule utterly divorced from the living world.

Section Nine: 上阳人,苦最多。少亦苦,老亦苦,少苦老苦两如何!君不见昔时吕向美人赋,又不见今日上阳白发歌!

Shàngyáng rén, kǔ zuì duō. Shào yì kǔ, lǎo yì kǔ, shào kǔ lǎo kǔ liǎng rúhé! Jūn bú jiàn xīshí Lǚ Xiàng měirén fù, yòu bú jiàn jīnrì Shàngyáng báifà gē!

Lady of Shangyang, yours is the bitterest lot. / Young, you suffered; old, you suffer—what is this double, damned knot! / Have you not seen the “Rhapsody on Beauties” by Lü Xiang of yore? / And do you not see today’s “Song of Shangyang, the White-Haired” once more?

The conclusion is a direct, impassioned summation. Suffering defines both her youth and age, negating any possible redemption. The allusion to Lü Xiang’s "Rhapsody on Beauties" masterfully juxtaposes the abstract, literary trope of the palace beauty with the concrete, aged reality of the "White-Haired" singer, asserting this poem as the necessary, truthful successor to all romanticized fictions—a lament for the innumerable real women whose lives were those fictions' cost.

Holistic Appreciation

This work is a pinnacle of Bai Juyi’s narrative art. Its achievement lies in using the intimate history of one life to illuminate the macro-cruelty of an entire institution. The poem, structured along the axis of lost time, traces the protagonist’s journey from sequestered hope through agonized consciousness to final numbness. The poet employs potent contrasts (youth/age, group/individual, past fashion/present mockery), immersive sensory details, and chilling statistics to render abstract injustice as palpable lived experience. Profoundly, the critique is not directed at a single malicious individual but at the system itself, granting the poem enduring, universal resonance.

Artistic Merits

- Seamless Fusion of Narrative and Lyricism: The first-person perspective creates powerful immediacy, while lyrical outbursts (e.g., "yours is the bitterest lot") frame and intensify the chronicle, blending epic scope with tragic intimacy.

- Masterful Compression of Time: Images like the interminable night, the sluggish day, and the cyclically indifferent moon condense decades of stagnant existence into a few crystalline, psychologically resonant moments.

- The Eloquence of Detail: Specifics—the green guards’ coats, the pointed shoes, the outdated makeup—function as potent symbols of confinement, temporal arrest, and institutional disregard.

- Potent Diction: The language is deceptively plain, yet word choices like "assigned," "condemned," and "ruined self" carry tremendous moral and emotional weight, creating tension through stark simplicity.

Insights

This poem is a timeless meditation on systemic isolation and the theft of a life’s purpose. It warns that any order which, in the name of service or stability, systematically negates individual dignity and severs the basic human connections to time, family, and society, is inherently brutal. The Lady of Shangyang’s tragedy is not merely imprisonment but erasure—her life becomes a "living blank" in history’s record. Bai Juyi’s act of writing is thus an act of ethical restitution, giving form to the formless and voice to the silenced. It challenges every society to measure its civility not by its palaces but by how it prevents the creation of its own "white-haired ladies"—those whom its systems have made invisible, timeless, and alone.

Poem translator

Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)

About the Poet

Bai Juyi (白居易), 772 - 846 AD, was originally from Taiyuan, then moved to Weinan in Shaanxi. Bai Juyi was the most prolific poet of the Tang Dynasty, with poems in the categories of satirical oracles, idleness, sentimentality, and miscellaneous rhythms, and the most influential poet after Li Bai Du Fu.