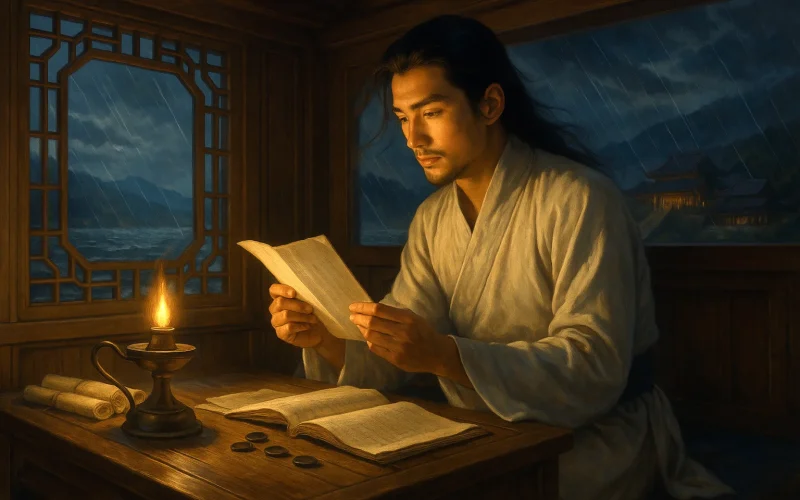

I read your book of poetry by the lamplight,

And finish it when oil burns low at dead of night.

Eyes sore, I blow the light out and sit in the dark;

The waves brought up by adverse wind beat on the bark.

Original Poem

「舟中读元九诗」

白居易

把君诗卷灯前读,诗尽灯残天未明。

眼痛灭灯犹暗坐,逆风吹浪打船声。

Interpretation

This poem was composed in the deep autumn of 815 AD, aboard the official boat carrying Bai Juyi to his demotion-post as Assistant Prefect of Jiangzhou. Months prior, his closest friend, Yuan Zhen, had also been demoted to Tongzhou. Both men now found themselves in the shared plight of "exiles at the world's edge." On a cold autumn night, on a solitary boat with a single lamp, the poet unfurled Yuan Zhen's scroll of poetry. Each character, each line, seemed the very visage of his old friend, stirring a complex and profound tide of emotion—deep longing for his companion, sorrowful lament for his own fate, and a silent, unvoiced protest against a world gone awry. Centered on the specific act of "reading poetry," the poem tightly interweaves the desolate chill of the external world with the turbulent surges of inner feeling, building layer upon layer to finally crystallize into a powerfully evocative portrait of the spirit, emblematic of the literature of exile in the Mid-Tang period.

First Couplet: 把君诗卷灯前读,诗尽灯残天未明。

Bǎ jūn shī juàn dēng qián dú, shī jìn dēng cán tiān wèi míng.

I hold your scroll of poems, reading by the lone lamp’s light; / The poems end, the lamp dies down, yet still it is not night.

Explication: The opening action is intensely specific; the verb "hold" carries a sense of treasuring. "Reading by the lone lamp’s light" sketches the sole warm and focused corner of solace in the cold night upon the solitary boat. The latter line, "The poems end, the lamp dies down, yet still it is not night" (literally: dawn has not come), creates a potent temporal predicament: the subjective mental activity (reading) is finished, yet the objective, drawn-out night is not. The lamp oil and the poetry are exhausted together, while dawn remains distant. Physical darkness and spiritual emptiness abruptly converge, and a sense of oppression pervades.

Second Couplet: 眼痛灭灯犹暗坐,逆风吹浪打船声。

Yǎn tòng miè dēng yóu àn zuò, nì fēng chuī làng dǎ chuán shēng.

My aching eyes force the lamp out; in darkness still I sit. / The sound of wind-lashed waves that pound this boat will not remit.

This couplet shifts from visual fatigue to acute hearing, from inward contemplation to external assault. "My aching eyes force the lamp out" marks a cessation compelled by physical limits; "in darkness still I sit" shows a mental turbulence that will not settle. Ultimately, all emotion and thought are absorbed and made concrete by "The sound of wind-lashed waves that pound this boat." This sound of wind and waves is both the actual scene before him and a symbolic roar embodying the poet's surging, unquiet anguish, the peril of his journey, the uncertainty of his future, and the obstructive force of a fate as contrary as a headwind. With irresistible physical force, it becomes the ultimate vessel and crescendo for the poem's emotion.

Holistic Appreciation

The poem's brilliance lies in constructing a complete emotional arc: from "focused immersion" to "vacant desolation" and finally to "internal tumult." The poem begins with "reading" and ends with "listening," forming a closed, intense loop of sensation and feeling. The first two lines, through the exhaustion of sight (reading till the lamp fails) and the suspension of time (dawn not coming), express the vast emptiness following the temporary end of a spiritual anchor. The final two lines, through physical fatigue (aching eyes), arrested action (sitting in darkness), and the dominance of hearing (the sound of waves), transform formless inner turmoil into a tangible, natural force. The emotional intensity deepens with each line, until that "sound… that pound[s] this boat" strikes not just the hull but resonates within the reader's heart, achieving a powerful portrayal of the exiled scholar's loneliness, grief, and fortitude.

Artistic Merits

- Emotion Through Concrete Action; Potent Detail: The entire poem clings to the central act of "reading poetry." A sequence of vivid, process-oriented details—"by the lamp's light," "poems end," "lamp dies down," "aching eyes," "force the lamp out," "sit in darkness"—renders abstract feelings (longing, loneliness, anguish) utterly concrete and profound.

- Unity of Environment and State of Mind: "The lamp dies down" corresponds to the pause in spiritual solace; "dawn not coming" symbolizes the obscurity of his prospects and the interminable wait; "wind-lashed waves" perfectly overlap the inner tempest with external adversity. The scenery is no mere backdrop but a direct reflection and extension of emotion.

- The Powerful Effect of an Auditory Conclusion: The poem concludes with the massive auditory image of "The sound of wind-lashed waves that pound this boat." This sound, both real and symbolic, cuts abruptly yet echoes endlessly. It pushes all emotion to a peak before leaving it for the reader to fathom, creating immense artistic impact.

- The Psychologizing of Time: "Dawn not coming" is not merely the hour; it is the poet's subjective perception of a darkening fate and his焦虑 for a light (hope, reunion) that will not arrive. Time is imbued with heavy psychological weight.

Insights

This poem reveals that in life's most arduous and loneliest hours, art—such as reading poetry—can serve as a bulwark against emptiness, while the sounds of nature, like wind and waves, can become the resonance and echo of our innermost feelings. Through the exchange and contemplation of poetic verses, the friendship between Bai Juyi and Yuan Zhen transcended physical distance, becoming each other's most steadfast spiritual solace in times of adversity.

It shows how genuine connection and comfort can traverse time and space, residing in a spiritual resonance. When confronting the headwinds of fate, one may, like the poet, seek solace and understanding in art, listen quietly to the tides within one’s own heart, and transform such experiences into a profound and enduring record of a life lived deeply. The power of this poem lies precisely in its ability to lift personal sorrow into a universal human expression of bonding, solitude, and perseverance—allowing us, a millennium later, to touch that enduring warmth and unyielding echo, both in the “lamp’s light” and in the “sound… that pounds.”

Poem translator

Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)

About the Poet

Bai Juyi (白居易), 772 - 846 AD, was originally from Taiyuan, then moved to Weinan in Shaanxi. Bai Juyi was the most prolific poet of the Tang Dynasty, with poems in the categories of satirical oracles, idleness, sentimentality, and miscellaneous rhythms, and the most influential poet after Li Bai Du Fu.