How beautiful she looks, opening the pearly casement,

And how quiet she leans, and how troubled her brow is!

You may see the tears now, bright on her cheek,

But not the man she so bitterly loves.

Original Poem

「怨情」

李白

美人卷珠帘,深坐蹙蛾眉。

但见泪痕湿,不知心恨谁?

Interpretation

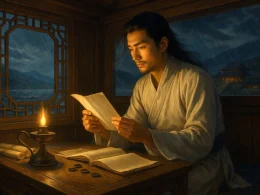

This poem is a representative work of Li Bai’s five-character quatrains on the theme of boudoir sorrow. Although its exact date of composition remains unknown, its concise and suggestive style reflects another dimension of Li Bai’s poetic art. Unlike his unrestrained and soaring works, this poem uses extremely spare brushstrokes and profound subtlety to capture a classic moment of emotion, showcasing the poet’s exceptional ability to grasp the delicate psychology of women.

First Couplet: “美人卷珠帘,深坐蹙蛾眉。”

Měirén juǎn zhūlián, shēn zuò cù éméi.

A beauty draws up the beaded curtain, then sits long and deep; Her moth-like brows are tightly knit in sorrow she will keep.

The opening uses two continuous actions to instantly draw the reader into a confined yet emotionally charged space. “Draws up the beaded curtain” is an act full of expectation—perhaps in hope of glimpsing someone, or an unconscious gesture of restlessness. Yet hope gives way to disappointment, leading to “sits long and deep.” The word “deep” suggests both the secluded place where she sits and the depth of her contemplation. “Her moth-like brows are tightly knit” externalizes her inner anguish into a visible expression. With just three images (beauty, beaded curtain, moth-brows) and three actions (draw, sit, knit), a complete scene and clear narrative emerge within ten characters.

Second Couplet: “但见泪痕湿,不知心恨谁?”

Dàn jiàn lèi hén shī, bù zhī xīn hèn shéi?

Only tear-streaks are seen, still damp and clear; Who the heart resents—none can know, none can hear.

The latter two lines shift from outward action to more nuanced observation. “Only… are seen” and “none can know” create a subtle contrast between what is visible and what remains unknown. The observer (the poet or the reader) can see the result of emotion (damp tear-streaks) but cannot determine its precise object. “Who the heart resents” is the poem’s striking stroke. Here, “resents” is not pure hatred, but a complex mingling of love, longing, and vexation. By leaving the object unspecified—whether an absent lover, an unfaithful partner, or merciless fate—the emotional space of the poem expands, allowing for countless possible stories and resonances.

Holistic Appreciation

The artistic power of this short poem lies in its “immense suggestion and precise framing.” Like a master painter, the poet captures only the most pregnant moment in an emotional tide—the disappointment after drawing up the curtain, the solitude of sitting alone, the distress of frowning in thought, the sadness of still-damp tears, and finally, all these feelings condensed into an irresolvable “resentment.” The poem never speaks of “sorrow,” yet sorrow is everywhere; it never mentions “longing,” yet longing fills every line.

The poem employs a classic progressive structure—“from movement to stillness, from external to internal”: from physical action (drawing the curtain), to a static posture (sitting deeply), to facial expression (frowning, tear-streaks), and finally pointing to the invisible inner heart (who the heart resents). This layered approach gradually draws the reader from observer into empathizer. The open-ended question of the last line elevates the poem from depicting a single person or event to profoundly touching a universal human emotional state, thus endowing it with timeless artistic vitality.

Artistic Merits

- Plain Depiction and the Force of Detail: It relies on plain description without allusions or embellishment. With only a few verbs—“draw,” “sit,” “knit,” “damp”—and a few nouns—“beaded curtain,” “moth-brows,” “tear-streaks”—it makes the figure come alive, showing a breathtaking power of immediacy.

- Art of Suspenseful Closure: “Who the heart resents—none can know, none can hear.” Ending with a question, left unanswered, creates strong artistic suspense. This uncertainty sparks the reader’s imagination and aftertaste more powerfully than any named object could, achieving the effect of “gaining all the grace without writing a word.”

- Enclosed Space and Pervasive Emotion: The scene is confined behind the “beaded curtain,” a narrow space, yet the figure’s “resentment,” directed at an unknown object, becomes boundless. This forms a potent contrast between a small physical space and immense emotional scope.

- Profound Insight into Feminine Psychology: Li Bai accurately captures the intricate psychological state of boudoir sorrow—the complex interweaving of love, hope, resentment, and longing—and condenses it into a still image, revealing his deep insight into the delicate layers of human feeling.

Insights

This poem is like a small window, offering a glimpse into those subtle, unspoken, and often elusive feelings in the human emotional world. It teaches us that the deepest emotions are often not loud but quiet; not clear but ambiguous. The question of whom the beauty resents is perhaps something everyone has experienced at some point—a nameless melancholy, a vague sense of loss, a tangled mix of love and grievance.

In today’s world, which prioritizes efficiency and clarity, this poem reminds us to cherish and understand those aspects of emotion that are difficult to name and cannot be simply attributed. It enlightens us that true empathy sometimes lies not in solving problems but in respecting and accompanying the complexity and authenticity of not knowing “who the heart resents.” This profound portrayal and respect for the subtle dimensions of human experience constitute another moving facet of Li Bai’s poetry beyond its heroic grandeur.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Li Bai (李白), 701 - 762 A.D., whose ancestral home was in Gansu, was preceded by Li Guang, a general of the Han Dynasty. Tang poetry is one of the brightest constellations in the history of Chinese literature, and one of the brightest stars is Li Bai.